The 2025–26 Transition Explained: How OBBA Resets the Rules for High-Income Households

.png)

If you’re a high-earning household, the tax code just changed in a way that’s easy to shrug off, and that’s exactly why it’s dangerous to ignore.

Most people I talk to are still working off an old mental model:

“Rates go up in 2026 when TCJA sunsets, SALT (State and Local Taxes) stays annoying, we’ll adjust later.”

That’s not the world we’re in anymore.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA), signed in July 2025, quietly rewired how the U.S. tax system treats high-income households for the next decade. It:

- Made key 2017 rate cuts effectively permanent

- Re-opened the SALT deduction in a very structured, phase-out-heavy way

- Raised estate and gift thresholds

- And then capped how much value top earners can get from itemized deductions starting in 2026

If you’re a high-income household, especially a tech family with concentrated equity, this isn’t “one more bill.” It’s a regime change.

The problem you’re solving for 2025–26 is not the one you were solving under a simple “TCJA sunsets and everything reverts” scenario.

Let’s break this down into the parts that actually matter to you.

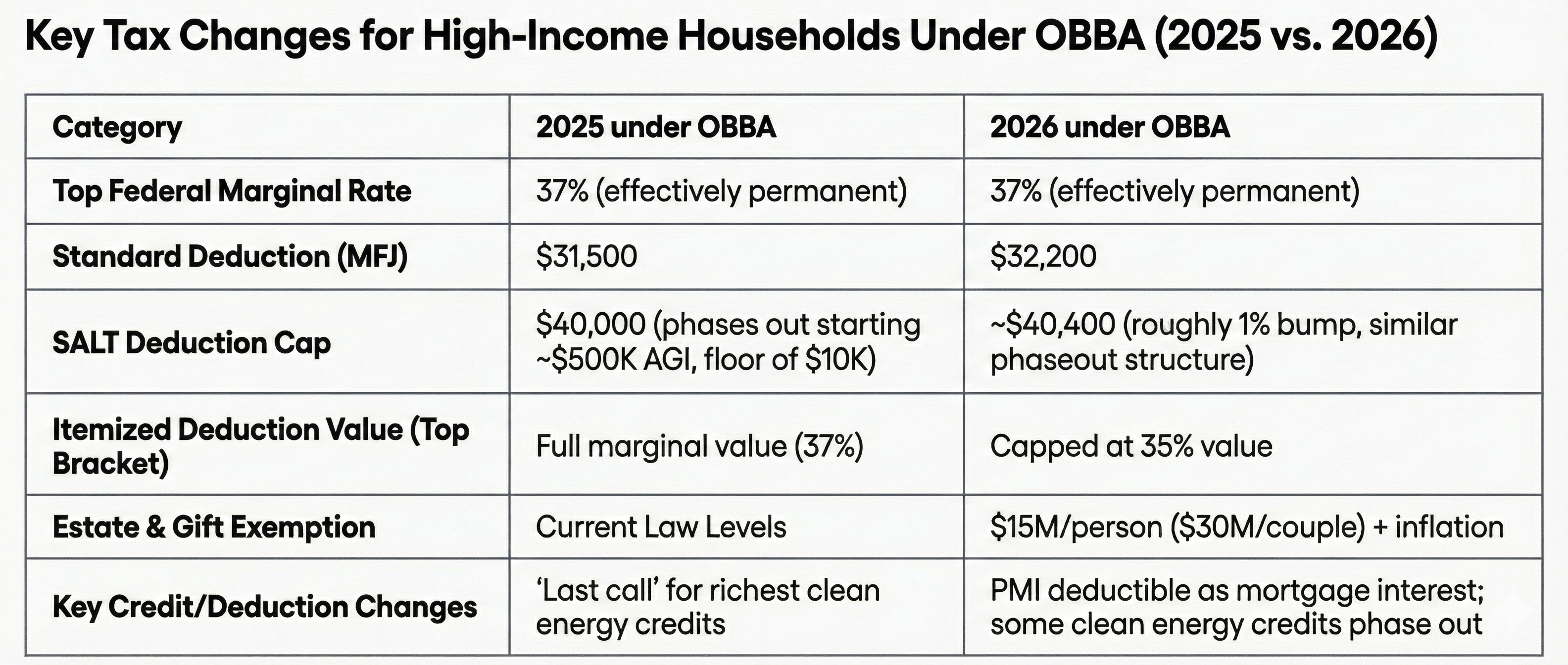

1. What OBBA actually changed (in the ways that matter to you)

I’ll skip the technical noise and focus on the levers that actually move your after-tax outcome.

1.1 Rates and the baseline

- The top federal marginal rate stays at 37% instead of reverting to 39.6% in 2026.

- Brackets continue to index with inflation as usual.

The standard deduction steps up again under OBBA:

- 2025: $31,500 for married filing jointly (MFJ), $15,750 single

- 2026: $32,200 MFJ, $16,100 single

So the default still nudges most people toward taking the standard deduction, unless your itemized deductions (SALT, mortgage interest, charitable giving, etc.) plus SALT are genuinely large.

For a lot of households, that means: if you’re going to itemize, you need to be deliberately over that bar, not accidentally near it.

1.2 SALT is back (sort of)

This is the headline change for high-tax-state households.

- The SALT cap jumps from $10,000 to $40,000 per return starting in 2025, with roughly 1% annual bumps through 2029.

- A phase-out starts around $500,000 of modified AGI for both singles and joint filers in 2025, with small inflation adjustments over time.

- Above that threshold, the SALT cap gets reduced, but never below $10,000.

Net effect:

- Upper-middle to “lower” high-income households in CA/NY/NJ and other high-tax environments finally see meaningful SALT relief.

- Ultra-high AGI households still feel pressure, but the picture is no longer a flat “$10k and that’s it.” It’s a curve that’s very sensitive to how you time income and deductions across years.

If you live in a high-tax state and own property, the shape of your income over time now matters more than the headline number in any single year.

1.3 Itemized deduction value caps (the 2026 “clip”)

Starting in 2026, OBBA introduces a constraint that doesn’t sound dramatic but has real consequences at the top:

- If you’re in the 37% bracket, the value of your itemized deductions is capped as if you were in a 35% bracket.

- In practice, that means roughly 35¢ of benefit per $1 deducted, instead of 37¢.

This doesn’t make itemizing pointless. But it reduces the marginal value of:

- SALT above the standard deduction

- Charitable contributions

- Mortgage interest and other large deductions

The practical takeaway:

2025 is the last clean year to get full-value itemized deductions at the top rate before this cap kicks in.

If you’re planning major charitable giving or large deductible moves anyway, ignoring that timing difference is a real miss.

1.4 Estate, gifting, and the “bigger box” for wealth transfer

OBBA resets the estate planning landscape:

- Estate & gift exemption moves to $15M per person ($30M per couple) starting in 2026, indexed for inflation thereafter.

Instead of bracing for a sharp drop in exemptions after a TCJA sunset, high-net-worth families now face:

- A larger, more stable exemption box

- A much clearer planning environment, which means: more of your peers will actually use it

If you’re sitting on concentrated tech equity, this is the regime in which:

- Entities

- Spousal trusts (like SLATs)

- And other trust-based strategies

become more common, not because they’re trendy, but because the rules are now defined enough to make multi-decade planning worthwhile.

1.5 Energy, housing, and timing-sensitive credits

OBBA also sends a very deliberate message about where it wants capital to flow:

- Several clean-energy credits and incentives phase out after 2025, especially for residential solar and efficiency upgrades.

- Mortgage interest rules are made permanent, and PMI becomes deductible as mortgage interest starting in 2026.

Translated:

- 2025 is a “last call” year for certain green upgrades and tax-efficient retrofits.

- The housing-related deduction framework is now stable enough to plan multi-year leverage, payoff, and refinancing strategies, without guessing what Congress might do in three years.

2. Think of OBBA as a new protocol, not a one-off patch

When something in your life fundamentally changes, a job, a city, a family situation, you don’t just keep running the old script. You pause and ask:

- What’s actually different now?

- What needs to change so things still work?

- What should I test before I lock anything in?

OBBA is that kind of change for high-income households.

The key question is no longer:

“What tax bracket am I in this year?”

It’s:

“Given OBBA, what belongs in 2025, what is smarter to push into 2026 - 29, and what kind of income or transactions should I avoid putting on my personal tax return at all if I can structure them differently?”

To make that concrete, I find it helpful to bucket the world into three windows.

2.1 Bucket the world into three windows

Here’s the framework I use:

2025: Full-value deduction year + SALT on-ramp

- SALT cap already at $40k

- Charitable + other itemized deductions still get full marginal value in the top bracket

- Certain clean energy and related credits are in their final, richest form

2026 - 2029: OBBA steady state

- SALT cap continues with modest increases; phaseouts step up slowly

- Itemized deduction benefit cap is live for top-bracket filers

- Estate exemption sits at the new $15M per person baseline (+ inflation)

2030+: Post-OBBA SALT sunset (under current law)

- SALT cap is scheduled to snap back to $10k

- Beyond that, you’re back in the realm of politics and speculation

If you’re a high-income household, the real planning questions become:

- Which actions are meaningfully better in 2025?

(Charitable bunching, SALT-heavy years, certain realization events.) - Which belong in the OBBA steady state?

(Estate moves, trust/entity structuring, long-duration planning.) - Which ideas look less attractive under OBBA because deduction caps blunt their payoff?

This is a multi-year scheduling problem, not a yearly “what do I deduct?” problem.

3. What changes specifically for high-income tech households

Let’s narrow this to the world I spend most of my time in: high-earning engineers, founders, and tech employees with complex equity.

3.1 SALT now interacts with your equity and geography

With a $40k SALT cap (before phaseouts), your:

- State

- Property tax profile

- Equity timing

all start talking to each other more than they did under the flat $10k cap.

In high-tax states (CA, NY, NJ, some city-tax-heavy areas), the expanded SALT cap can be real money if:

- Your AGI clusters in the $300k–$600k band, and

- You own a home or have meaningful state tax exposure.

Above that range, the phase-outs matter. You’re effectively incentivized to:

- Avoid spiking AGI in a single year that pushes you well past the ~$500k threshold and erodes SALT value

- Think harder about when you recognize income where you have discretion:

- Option exercises

- Secondaries

- Structured exits

- RSU sales beyond normal vesting cadence

Practically, this makes multi-year planning for RSUs, ISO exercises, and tender offers more critical. You’re no longer just picking lower rates; you’re navigating SALT caps, phaseouts, and deduction value caps at the same time.

3.2 Charitable and “big swing” years in 2025

Because 2026+ limits the benefit of itemized deductions for top-bracket filers, 2025 becomes a privileged year for moves you were likely going to make anyway, such as:

- Larger charitable contributions (including donor-advised funds)

- Stacking or “bunching” itemized deductions:

- Property tax (where prepayment is allowed)

- Medical or other deductible expenses you can time

- Certain Roth conversion strategies, if you can pair them with high-value deductions

I’m not saying you should force everything into 2025. What I’m saying is:

If you already expect big deductible events, not comparing 2025 vs 2026 treatment is a missed opportunity.

3.3 Estate planning stops being “later”

For a lot of millennial millionaires, estate planning has historically felt like a “future problem.”

OBBA changes the calculus:

- A clearly defined $15M per-person exemption from 2026 provides enough stability to actually design around, instead of waiting to “see what Congress does.”

- The interaction of the SALT regime + trust planning in high-tax states creates situations where income tax planning and estate tax planning overlap in useful ways.

If you’re sitting on $5 - 15M of equity (liquid + illiquid), ignoring this is no longer just procrastination; it’s ignoring a structurally better planning environment that now exists in your favor.

4. How we think about OBBA as a systems problem

At Alphanso, we don’t treat this as a list of “tax tricks.” We treat it like a systems problem.

If I were sketching an OBBA-aware engine on a whiteboard for a client, I’d break it into three layers.

4.1 Law → Features: turning OBBA into data

First layer: turn the law into structured data.

From OBBA and IRS guidance, you can extract features like, for each year:

- Bracket thresholds, rates, AMT parameters

- SALT cap, its inflation path, and the phaseout formula as a function of modified AGI

- Itemized deduction benefit caps for top brackets

- Estate & gift exemption levels

- Credit and deduction windows (sunset dates, phaseout ranges, etc.)

That becomes a versioned feature store of the tax code: machine-readable, year-by-year.

4.2 Multi-year simulation: where should each dollar live?

Second layer: stop thinking in single-year snapshots.

For a given household, you simulate:

- Income timelines:

W-2, RSUs, bonuses, equity events, spouse income - Deduction timelines:

SALT accumulation by state, mortgage interest, charitable intent, potential trust/entity structures - Asset trajectories:

Concentrated equity, retirement accounts, taxable portfolios

Then you ask questions like:

- If we realize $1M of long-term gains in 2025 vs 2026, what changes after tax once we include SALT, charitable plans, and deduction caps?

- If we accelerate a charitable commitment into 2025, how does that change the ideal timing for a Roth conversion or a secondary sale?

- If we move from CA to WA in mid-2026, what’s the best sequence for option exercises relative to that move and the SALT regime?

At that point, you’re not doing “tax tips.” You’re doing:

Constrained multi-year optimization under a piecewise tax function defined by OBBA.

That’s not something you reliably brute-force on a napkin.

4.3 Personalization: not “what’s optimal?” but “what’s sensible for you?”

Third layer: what’s technically optimal is not always what’s right for your life.

Two households with identical income can make very different choices because:

- One is comfortable with K-1s and trusts; the other wants simplicity.

- One expects another liquidity event in three years; the other plans to slow down.

- One has strong ethical views on certain investment types; the other is more agnostic.

So any serious system needs to incorporate:

- Behavioral preferences (what you consistently accept or reject)

- Hard constraints (ethical, regulatory, personal)

- Liquidity needs and psychological risk tolerance

This is where “AI for wealth” has a legitimate role, not in inventing clever hacks, but in sorting through more moving parts than any one person can comfortably track, and doing it in a way that still feels explainable.

5. What to do with all this (without turning it into homework)

I don’t think the right reaction to OBBA is:

“Drop everything and re-engineer your life around the SALT cap.”

The more grounded takeaways are:

- 2025 is not just another year.

It’s the last year before deduction caps bite for top earners and the first year of the expanded SALT regime. It deserves a deliberate plan, not an autopilot filing. - Stop thinking in one-year clips.

Most meaningful moves, RSU liquidation, startup exits, relocation, major philanthropy, estate work, are multi-year by nature. OBBA simply made the math explicitly multi-year. - Generic calculators won’t cut it.

The way your equity, state, housing, and goals stack together is too specific for broad rules of thumb. This is exactly where a proper data and modeling stack, plus human judgment, outperforms “I read something in an article once.”

Closing thought

For years, high-earning households were handed a simple narrative:

“Yes, tax law is noisy, but the playbook is stable.

Max your 401(k), buy the index, bunch deductions occasionally, you’ll be fine.”

OBBA quietly broke that story.

When the law introduces:

- Time-boxed SALT relief

- Permanent but constrained deductions for top earners

- A clearly defined estate regime at higher thresholds

it’s sending a very specific message:

The default path for a high-income household now looks meaningfully different depending on how you route cash flows across years, entities, and states.To me, the interesting question is no longer:

“What’s my tax bracket?”

It’s:

“Given OBBA, how do we build systems that continuously ingest this new regime, my real-world constraints, and market dynamics, and then surface a small, clear set of high-confidence, explainable moves?”

If most of your upside lives in complex equity and high-tax jurisdictions, treating OBBA as a footnote is risky.

If this resonates, and you’d rather have a team look at your entire system instead of one account or one metric in isolation, you can schedule a 1:1 session with our advisory team.

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)